The Brokenhearted

Whalemen’s Club

—

Kevin Maloney

I WENT TO TACOMA TO VISIT my buddy Aaron, who was on sabbatical from his professor job at the University of Michigan, because I was going through a divorce and needed to be near water—specifically the Puget Sound, that glorious inlet of ocean teeming with orcas and salmon due west of Seattle. As a child, my grandfather piloted us around that body of water in his boat, deep sea fishing, pulling snapper out of the ocean, their eyes bulging from the pressure change. I wanted to feel like that again—not like the snapper, but the child version of me, before I got married twice and divorced once, with the second divorce pending the approval of a mediator, two attorneys, and a Multnomah County judge.

Aaron and I sat in the courtyard of his AirBNB, drinking cheap beer, talking about how when you are going through a divorce, it’s like God has you pinned to a rock and is sawing your appendages off one by one, drawing smiley faces in the sand with your blood, but then afterwards, once you’re just stumps, shriveled up without any liquid inside of you, dead, your torso becomes the seed of a future life even better than the one that came before it.

“Like… I know that’s true,” I said, a bubble of snot ballooning over my left nostril. “But right now, it’s just me and God and the saw.”

“Saw-phase is the hardest,” said Aaron. “Hey, I have an idea. Let’s go to the waterfront. Maybe we’ll see a pack of orcas.”

“They’re called pods,” I said.

“Which is another name for seeds, am I right?”

We finished our beers and walked a quarter of a mile to the waterfront.

The Sound was breathtaking—a panoramic view of ocean with mounds of vibrant green land rising out of the water, speckled with mansions occupied by retired Microsoft and Amazon employees. To the east was Mt. Rainier, that great white phantom like Moby Dick rising from the choppy sea.

“Mountain’s out,” said Aaron, which was Pacific Northwest code for “We hate California.”

I nodded and said, “Yeah, it’s glorious,” which was Pacific Northwest code for “Can you imagine living in L.A.? I’d rather be dead.”

Joggers ran in both directions on wide paths, zipping past non-joggers eating ice cream cones. Transplants from Southern California rollerbladed in neon jumpsuits, mistaking this part of the world for a place where people were happy. A husband and wife rode around in a pedal-powered cruiser, but they were fighting because the wife was pedaling harder than the husband, which caused them to go around and around in circles.

“That used to be me,” I said, pointing at the quarreling couple.

“Right?” said Aaron. “But now you are like one of those rollerbladers. Solo and free.”

“Fuck rollerbladers,” I said.

“Okay, well maybe more like one of those joggers.”

“I like the treadmill to be honest,” I said. “There’s a function at the gym where you can make the screen look like you’re jogging in Thailand. I prefer my VR Thai jogs.”

“Well then you’re like Kevin fucking Maloney, sad and free in a flannel and Pearl Jam shirt, hanging out with Aaron fucking Burch next to the ocean where we’re going to gather a bunch of orca pods and plant them in the garden of your future.”

It was the most beautiful thing that anyone had ever said to me. I gave Aaron a fist bump and said, “Ken Griffey, Jr.”

He gave me a fist bump back and said, “Clyde Drexler,” which is how men in their 40s from this part of the world say, “I fucking love you, man.”

“We should have brought beer with us,” I said, looking at my hand, noticing that it wasn’t holding anything that could get me drunk.

Aaron said, “I feel like we should switch things up and drink something that isn’t alcohol? For instance, isn’t water supposed to be good for you?”

We tried to find a store to buy water, but it was just a bunch of people exercising and the couple in the pedal-powered cruiser going around and around in circles.

“Tell me if this is a dumb idea,” said Aaron. “But what if we drink the Puget Sound?”

“That’s salt water,” I said. “It just makes you thirstier.”

“Sure,” said Aaron. “I mean… if you believe in science or whatever. But we’re from the Pacific Northwest. I feel like our bodies will know what to do with it.”

I thought about arguing with Aaron, but then I looked up and saw God leaning down with a giant saw, his eyes full of darkness and fire.

“Sure,” I said. “Fuck it.”

We ambled down a bunch of black rocks. The tide was out. The rocks were covered in barnacles and shells and starfish.

I pulled a starfish off a rock. “Should we eat one of these?” I asked.

“That feels right,” said Aaron.

We each broke an arm off the starfish and ate it. The tiny spikes made our mouths bleed, and the sticky legs wreaked havoc on our tongues, but when we looked at each other with blood dribbling down our chins, we felt like men—lumberjacks from a part of the world where the trees are so tall they stick out of the earth’s atmosphere and whack against the moon.

“I want to eat a spotted owl next,” said Aaron.

“I want to eat the tree the owl lives in,” I said.

We looked down at the three-legged starfish and started to feel bad, but then two arms regrew in its place.

“Did that actually just happen?” asked Aaron.

“I think so?” I said. “Wait—is this an infinite food source?”

It was incredible. Our whole life we’d been going to jobs to make enough money to pay for food, a depressing routine that had seriously cut into our writing time. Instead of going to work, depositing checks, and going to the grocery store, we could have been taking turns eating legs off a single starfish while sitting at our laptops, writing the Great American Novel.

I put the starfish in my pocket and stepped out into the ocean. It was cold and smelled like kelp and dead fish. I lowered my mouth in the water and drank. Aaron did the same. At first it tasted like the blood from the roofs of our mouths, but then it tasted like saline and seagull droppings.

“This will probably make us sick,” said Aaron.

“Oh, definitely,” I said.

“I feel like we’re going to regret this later, but it feels so good right now.”

“I’ve never felt more connected to this land our ancestors stole from indigenous people so that we could rent AirBNBs next to the ocean and pretend we are communing with nature to heal from past and current heartaches.”

We looked out at the water that was supposedly full of orcas, but was, at the moment, covered in the yachts of billionaires retired from Microsoft and Amazon.

“We should probably be on one of those boats if we want to see the orcas and not here in the muck with bloody mouths and bacteria in our digestive systems,” said Aaron.

“Yeah, they have a better vantage point,” I admitted.

“Okay, hear me out,” said Aaron. “Maybe this idea is even stupider than my idea to drink ocean water, but like… what if we swam out to one of those boats and asked them to let us hang out with them because we’re famous writers?”

“Are we famous writers?” I asked.

“Well, no. But most people don’t read books. They won’t know the difference.”

“That’s a really good point,” I said.

We plunged into the water and started swimming. Aaron had a magnificent technique, circling his arms in rapid succession, his head exhaling bubbles like an Olympian. My technique involved doggy-paddling and using an empty water bottle I found to help keep me from sinking to the bottom of the ocean.

“Wait, can you not swim?” asked Aaron from a hundred feet in front of me.

“This is swimming,” I said. “I mean… I don’t feel like I’m drowning.”

Aaron pulled up alongside a yacht with the name “Pequod” written on the side. He made a bunch of hand motions, and the crew hoisted him onto the deck. A minute later, a guy on a jet ski pulled up alongside me and gave me a ride to the boat.

The owners were a husband and wife—George and Betty. They’d invested in Starbucks when it was a single coffee shop on Pike Place and Microsoft when it was a single nerd soldering wires in his garage and Amazon when Jeff Bezos still had hair.

We told them about our novels and our story collections, and they promised to buy our books from their friend Jeff’s website, although they admitted they hardly ever read and honestly didn’t even realize that people still wrote books, which they understood to be an antiquated activity like alchemy or jousting.

One of the crew members showed up with a tray of margaritas.

“Drink up, Shakespeare!” squealed Betty. “You too, Hemingway.”

“Kevin’s more like Richard Brautigan,” said Aaron. “But Hemingway works too. He’s going through a divorce.”

“Oh, wow,” said George. “That’s going to be tricky dividing up all that writer money.”

“Super tricky,” I said. “Whole teams of lawyers involved. Because of all that money I make from writing books.”

“We’re hoping to see orcas,” said Aaron. “I feel like Kevin won’t get back on his feet until he gets a good look at those black and white sea cows.”

“More like monsters,” said George. “Did you know those bastards drown baby gray whales?”

“It’s nature,” said Aaron. “Nature is good for you when you’re going through a divorce. Even the murder-y parts.”

The billionaire picked up a walkie talkie. “Hey, Ahab. This is George. This guy we picked up wants to see some orcas. Can you make that happen?”

“Wait, what’s the captain’s name?” I asked.

“Ahab,” said George. “Strange, right?”

“Like from Moby Dick?” I asked.

George gave me a blank look and lit a cigar. Betty lit a hundred dollar bill on fire just for fun.

I looked up to the captain’s deck and noticed a scowling man pacing back and forth, fiercely gripping a walkie talkie. He had a dark beard and no mustache and a false leg made of whale bone.

I nudged Aaron and pointed to the captain.

Aaron said, “Yeah, I saw. But like—he’s nature too. All of this is nature.”

The yacht’s engines fired, and we made our way to deeper waters off the coast of Victoria.

Eventually, Ahab appeared from the captain’s quarters and began scanning the horizon through a brass telescope.

“My drink is broken,” said Betty, rattling ice cubes around her empty glass. “Call Starbuck and have him mix us another round.”

“Starbuck?” I asked.

“I know!” said George. “Funny right? Just like the coffee shop.”

A man in a striped shirt and knit cap appeared with a tray covered in cocktails. “For ye thirsty wenches!” he said.

“Isn’t his accent funny?” whispered Betty.

“Thar she blows!” cried Ahab from the captain’s deck.

We all turned at once. There they were—a dozen black fins rising and falling in rhythm like the ecstatic undulations of a single subaquatic animal. The water sprayed off their backs and formed rainbows above the water.

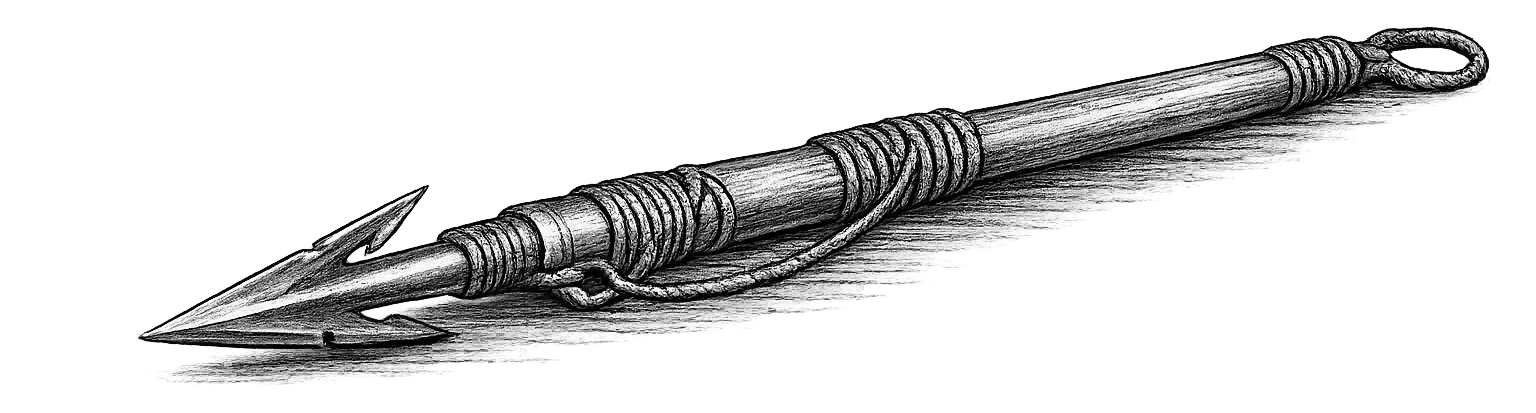

Ahab revved the engine. The yacht began skipping on the surface of the Sound. Starbuck took over the steering wheel. Ahab appeared next to us holding a long spear terminating in a menacing hook.

“Come now, Ahab,” said Betty. “We just want to look at them.”

“But… they drown baby gray whales,” said Ahab.

“It’s nature,” said Aaron. “All of this. Even this margarita. Speaking of which—am I catching a note of smoke? Is there mezcal in here?”

“Just one!” said Ahab. “Let me kill just one.”

I looked into Ahab’s eyes and understood. “What was her name?” I asked.

“Who?” snarled Ahab.

“The woman who broke your heart,” I said.

Ahab started sobbing. “Sarah,” he whispered.

We retreated to the captain’s quarters. Ahab lit a fire in the fireplace and poured me a glass of scotch.

“She was a fearsome wench,” said Ahab. “Probably still is, but some other man gets to enjoy all that fury now. She used to bite my nose when I slept. Once she attacked me with a staple gun because I was trying to fix her problems rather than empathizing.”

“Anne hired a hitman to kill me one time,” I said. “He broke into our house and pressed the barrel of a shotgun into my mouth. At the last second, Anne said, ‘Wait! Stop! I just want you to unfurl your socks before you put them in the washing machine. Otherwise they don’t get clean and make the other laundry smell like dirty feet.’”

“She sounds perfect,” said Ahab, taking a sip of scotch. “But we know how it goes. It gets to be too much. Your therapist says you aren’t honoring yourself by staying in the relationship. I stuck around too long… until I lost the leg.”

I laughed, but Ahab wasn’t joking.

“I tell people it was a whale. A white one! No. It was Sarah. She caught me looking at internet porn and drugged me and cut it off with a hacksaw while I slept. I’m out here piloting billionaires around, scanning the horizon for spouts, but really I’m looking for Sarah. What a woman.”

I offered Ahab my starfish. He ripped an arm off and handed it back to me. I ripped one off and pressed my teeth into the spiky appendage. We raised our glasses and drank to all the harm that had been done to us by wives so pretty they made our insides hurt.

Aaron was right—all of this was medicine. Harpoons, hacksaws, the cries of the gray whale baby sinking to the ocean floor like a stone.

I felt my stomach burn with scotch. A numbness took over. For the first time since my divorce, I imagined a life beyond Anne. A life full of scars and missing limbs where you never stopped thinking about your ex and got a job piloting a boat around the most beautiful place in the world, killing innocent beasts to alleviate the pain of your unhealthy, toxic marriage, but a life nonetheless.

In the distance, I heard Aaron’s voice calling. He was worried. He didn’t know that God’s work was done. My limbs were sawed off clean. Ahab and I were brothers now, sitting in the fire’s dancing light, drinking ourselves to death so we could find out once and for all if anything would grow from our broken, withered hearts. •

![]()

![]()

Kevin Maloney is the author of Horse Girl Fever, The Red-Headed Pilgrim, and Cult of Loretta. His writing has appeared in Fence, HAD, Forever Magazine, and a number of other journals and anthologies. He is the co-founder and fiction editor of Pool Party, which he runs with his wife, writer and artist Ryan-Ashley Anderson Maloney. They live together in Portland, Oregon, with their one-eyed dog and three cats.

Website | Bluesky | Instagram

Aaron and I sat in the courtyard of his AirBNB, drinking cheap beer, talking about how when you are going through a divorce, it’s like God has you pinned to a rock and is sawing your appendages off one by one, drawing smiley faces in the sand with your blood, but then afterwards, once you’re just stumps, shriveled up without any liquid inside of you, dead, your torso becomes the seed of a future life even better than the one that came before it.

“Like… I know that’s true,” I said, a bubble of snot ballooning over my left nostril. “But right now, it’s just me and God and the saw.”

“Saw-phase is the hardest,” said Aaron. “Hey, I have an idea. Let’s go to the waterfront. Maybe we’ll see a pack of orcas.”

“They’re called pods,” I said.

“Which is another name for seeds, am I right?”

We finished our beers and walked a quarter of a mile to the waterfront.

The Sound was breathtaking—a panoramic view of ocean with mounds of vibrant green land rising out of the water, speckled with mansions occupied by retired Microsoft and Amazon employees. To the east was Mt. Rainier, that great white phantom like Moby Dick rising from the choppy sea.

“Mountain’s out,” said Aaron, which was Pacific Northwest code for “We hate California.”

I nodded and said, “Yeah, it’s glorious,” which was Pacific Northwest code for “Can you imagine living in L.A.? I’d rather be dead.”

Joggers ran in both directions on wide paths, zipping past non-joggers eating ice cream cones. Transplants from Southern California rollerbladed in neon jumpsuits, mistaking this part of the world for a place where people were happy. A husband and wife rode around in a pedal-powered cruiser, but they were fighting because the wife was pedaling harder than the husband, which caused them to go around and around in circles.

“That used to be me,” I said, pointing at the quarreling couple.

“Right?” said Aaron. “But now you are like one of those rollerbladers. Solo and free.”

“Fuck rollerbladers,” I said.

“Okay, well maybe more like one of those joggers.”

“I like the treadmill to be honest,” I said. “There’s a function at the gym where you can make the screen look like you’re jogging in Thailand. I prefer my VR Thai jogs.”

“Well then you’re like Kevin fucking Maloney, sad and free in a flannel and Pearl Jam shirt, hanging out with Aaron fucking Burch next to the ocean where we’re going to gather a bunch of orca pods and plant them in the garden of your future.”

It was the most beautiful thing that anyone had ever said to me. I gave Aaron a fist bump and said, “Ken Griffey, Jr.”

He gave me a fist bump back and said, “Clyde Drexler,” which is how men in their 40s from this part of the world say, “I fucking love you, man.”

“We should have brought beer with us,” I said, looking at my hand, noticing that it wasn’t holding anything that could get me drunk.

Aaron said, “I feel like we should switch things up and drink something that isn’t alcohol? For instance, isn’t water supposed to be good for you?”

We tried to find a store to buy water, but it was just a bunch of people exercising and the couple in the pedal-powered cruiser going around and around in circles.

“Tell me if this is a dumb idea,” said Aaron. “But what if we drink the Puget Sound?”

“That’s salt water,” I said. “It just makes you thirstier.”

“Sure,” said Aaron. “I mean… if you believe in science or whatever. But we’re from the Pacific Northwest. I feel like our bodies will know what to do with it.”

I thought about arguing with Aaron, but then I looked up and saw God leaning down with a giant saw, his eyes full of darkness and fire.

“Sure,” I said. “Fuck it.”

We ambled down a bunch of black rocks. The tide was out. The rocks were covered in barnacles and shells and starfish.

I pulled a starfish off a rock. “Should we eat one of these?” I asked.

“That feels right,” said Aaron.

We each broke an arm off the starfish and ate it. The tiny spikes made our mouths bleed, and the sticky legs wreaked havoc on our tongues, but when we looked at each other with blood dribbling down our chins, we felt like men—lumberjacks from a part of the world where the trees are so tall they stick out of the earth’s atmosphere and whack against the moon.

“I want to eat a spotted owl next,” said Aaron.

“I want to eat the tree the owl lives in,” I said.

We looked down at the three-legged starfish and started to feel bad, but then two arms regrew in its place.

“Did that actually just happen?” asked Aaron.

“I think so?” I said. “Wait—is this an infinite food source?”

It was incredible. Our whole life we’d been going to jobs to make enough money to pay for food, a depressing routine that had seriously cut into our writing time. Instead of going to work, depositing checks, and going to the grocery store, we could have been taking turns eating legs off a single starfish while sitting at our laptops, writing the Great American Novel.

I put the starfish in my pocket and stepped out into the ocean. It was cold and smelled like kelp and dead fish. I lowered my mouth in the water and drank. Aaron did the same. At first it tasted like the blood from the roofs of our mouths, but then it tasted like saline and seagull droppings.

“This will probably make us sick,” said Aaron.

“Oh, definitely,” I said.

“I feel like we’re going to regret this later, but it feels so good right now.”

“I’ve never felt more connected to this land our ancestors stole from indigenous people so that we could rent AirBNBs next to the ocean and pretend we are communing with nature to heal from past and current heartaches.”

We looked out at the water that was supposedly full of orcas, but was, at the moment, covered in the yachts of billionaires retired from Microsoft and Amazon.

“We should probably be on one of those boats if we want to see the orcas and not here in the muck with bloody mouths and bacteria in our digestive systems,” said Aaron.

“Yeah, they have a better vantage point,” I admitted.

“Okay, hear me out,” said Aaron. “Maybe this idea is even stupider than my idea to drink ocean water, but like… what if we swam out to one of those boats and asked them to let us hang out with them because we’re famous writers?”

“Are we famous writers?” I asked.

“Well, no. But most people don’t read books. They won’t know the difference.”

“That’s a really good point,” I said.

We plunged into the water and started swimming. Aaron had a magnificent technique, circling his arms in rapid succession, his head exhaling bubbles like an Olympian. My technique involved doggy-paddling and using an empty water bottle I found to help keep me from sinking to the bottom of the ocean.

“Wait, can you not swim?” asked Aaron from a hundred feet in front of me.

“This is swimming,” I said. “I mean… I don’t feel like I’m drowning.”

Aaron pulled up alongside a yacht with the name “Pequod” written on the side. He made a bunch of hand motions, and the crew hoisted him onto the deck. A minute later, a guy on a jet ski pulled up alongside me and gave me a ride to the boat.

The owners were a husband and wife—George and Betty. They’d invested in Starbucks when it was a single coffee shop on Pike Place and Microsoft when it was a single nerd soldering wires in his garage and Amazon when Jeff Bezos still had hair.

We told them about our novels and our story collections, and they promised to buy our books from their friend Jeff’s website, although they admitted they hardly ever read and honestly didn’t even realize that people still wrote books, which they understood to be an antiquated activity like alchemy or jousting.

One of the crew members showed up with a tray of margaritas.

“Drink up, Shakespeare!” squealed Betty. “You too, Hemingway.”

“Kevin’s more like Richard Brautigan,” said Aaron. “But Hemingway works too. He’s going through a divorce.”

“Oh, wow,” said George. “That’s going to be tricky dividing up all that writer money.”

“Super tricky,” I said. “Whole teams of lawyers involved. Because of all that money I make from writing books.”

“We’re hoping to see orcas,” said Aaron. “I feel like Kevin won’t get back on his feet until he gets a good look at those black and white sea cows.”

“More like monsters,” said George. “Did you know those bastards drown baby gray whales?”

“It’s nature,” said Aaron. “Nature is good for you when you’re going through a divorce. Even the murder-y parts.”

The billionaire picked up a walkie talkie. “Hey, Ahab. This is George. This guy we picked up wants to see some orcas. Can you make that happen?”

“Wait, what’s the captain’s name?” I asked.

“Ahab,” said George. “Strange, right?”

“Like from Moby Dick?” I asked.

George gave me a blank look and lit a cigar. Betty lit a hundred dollar bill on fire just for fun.

I looked up to the captain’s deck and noticed a scowling man pacing back and forth, fiercely gripping a walkie talkie. He had a dark beard and no mustache and a false leg made of whale bone.

I nudged Aaron and pointed to the captain.

Aaron said, “Yeah, I saw. But like—he’s nature too. All of this is nature.”

The yacht’s engines fired, and we made our way to deeper waters off the coast of Victoria.

Eventually, Ahab appeared from the captain’s quarters and began scanning the horizon through a brass telescope.

“My drink is broken,” said Betty, rattling ice cubes around her empty glass. “Call Starbuck and have him mix us another round.”

“Starbuck?” I asked.

“I know!” said George. “Funny right? Just like the coffee shop.”

A man in a striped shirt and knit cap appeared with a tray covered in cocktails. “For ye thirsty wenches!” he said.

“Isn’t his accent funny?” whispered Betty.

“Thar she blows!” cried Ahab from the captain’s deck.

We all turned at once. There they were—a dozen black fins rising and falling in rhythm like the ecstatic undulations of a single subaquatic animal. The water sprayed off their backs and formed rainbows above the water.

Ahab revved the engine. The yacht began skipping on the surface of the Sound. Starbuck took over the steering wheel. Ahab appeared next to us holding a long spear terminating in a menacing hook.

“Come now, Ahab,” said Betty. “We just want to look at them.”

“But… they drown baby gray whales,” said Ahab.

“It’s nature,” said Aaron. “All of this. Even this margarita. Speaking of which—am I catching a note of smoke? Is there mezcal in here?”

“Just one!” said Ahab. “Let me kill just one.”

I looked into Ahab’s eyes and understood. “What was her name?” I asked.

“Who?” snarled Ahab.

“The woman who broke your heart,” I said.

Ahab started sobbing. “Sarah,” he whispered.

We retreated to the captain’s quarters. Ahab lit a fire in the fireplace and poured me a glass of scotch.

“She was a fearsome wench,” said Ahab. “Probably still is, but some other man gets to enjoy all that fury now. She used to bite my nose when I slept. Once she attacked me with a staple gun because I was trying to fix her problems rather than empathizing.”

“Anne hired a hitman to kill me one time,” I said. “He broke into our house and pressed the barrel of a shotgun into my mouth. At the last second, Anne said, ‘Wait! Stop! I just want you to unfurl your socks before you put them in the washing machine. Otherwise they don’t get clean and make the other laundry smell like dirty feet.’”

“She sounds perfect,” said Ahab, taking a sip of scotch. “But we know how it goes. It gets to be too much. Your therapist says you aren’t honoring yourself by staying in the relationship. I stuck around too long… until I lost the leg.”

I laughed, but Ahab wasn’t joking.

“I tell people it was a whale. A white one! No. It was Sarah. She caught me looking at internet porn and drugged me and cut it off with a hacksaw while I slept. I’m out here piloting billionaires around, scanning the horizon for spouts, but really I’m looking for Sarah. What a woman.”

I offered Ahab my starfish. He ripped an arm off and handed it back to me. I ripped one off and pressed my teeth into the spiky appendage. We raised our glasses and drank to all the harm that had been done to us by wives so pretty they made our insides hurt.

Aaron was right—all of this was medicine. Harpoons, hacksaws, the cries of the gray whale baby sinking to the ocean floor like a stone.

I felt my stomach burn with scotch. A numbness took over. For the first time since my divorce, I imagined a life beyond Anne. A life full of scars and missing limbs where you never stopped thinking about your ex and got a job piloting a boat around the most beautiful place in the world, killing innocent beasts to alleviate the pain of your unhealthy, toxic marriage, but a life nonetheless.

In the distance, I heard Aaron’s voice calling. He was worried. He didn’t know that God’s work was done. My limbs were sawed off clean. Ahab and I were brothers now, sitting in the fire’s dancing light, drinking ourselves to death so we could find out once and for all if anything would grow from our broken, withered hearts. •

Kevin Maloney is the author of Horse Girl Fever, The Red-Headed Pilgrim, and Cult of Loretta. His writing has appeared in Fence, HAD, Forever Magazine, and a number of other journals and anthologies. He is the co-founder and fiction editor of Pool Party, which he runs with his wife, writer and artist Ryan-Ashley Anderson Maloney. They live together in Portland, Oregon, with their one-eyed dog and three cats.

Website | Bluesky | Instagram